“The Work of Art on the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” by Walter Benjamin was published in 1936, the inter war period. “Having experienced Fascism and the fascist use of media in Germany” [from Media & Cultural Studies Keyworks ed. by Durham and Kellner] Benjamin speaks to the transformation of the Marxian superstructure which he observed “has taken more than a half century to manifest in all areas of culture the change in the conditions of production”. Reflecting on the function of art in the 20th century, he explores a theory of art and the “useful formulation of revolutionary demands in the politics of art.” [Preface] Since first reading this essay fifteen years ago, I’ve always been struck by its prescience and continual resonance in the digital age, so please forgive the length of this provocation beyond the recommended 2-3 paragraph blog post.

Benjamin asserts that the work of art has always been reproducible, but is quick to point out that mechanical reproduction, i.e., Marxian Capitalist mechanistic reproduction, through photography and film, represents something new. Benjamin discusses the profound repercussions that reproduction of works of art through photography, and the ‘art of the film’ have had on art in its traditional form. [Section I] Given this context, what are your thoughts on Benjamin’s statement that “even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be,” or in Benjamin-ian terms, its “aura”. [Section II] Benjamin further clarifies and defines the term “aura” of the work of art as “that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction”. Do you agree or disagree?

For this provocation, I’ll use an example from art: does Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa cease to be the Mona Lisa if we remove her from the rooms in which Leonardo painted and her patron intended her or the Louvre where she has resided for many centuries and still resides today? For example, more specifically, an enlarged and interactive Mona Lisa is currently on display in the windows of fashion conglomerate LVMH at 5th Ave. and 57th Street and she even winks. She is featured in a collection of luxury leather products designed by artist Jeff Koons entitled “MASTERS” that retails for approx. $585.00 – $4,000.00. Here’s a recent photo of the display:

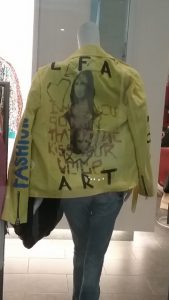

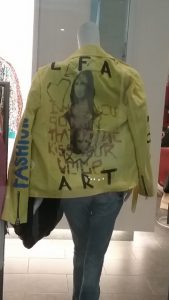

Mona Lisa is also currently on display at my local mall via a jacket design:

Do you think such reproduction erodes, or conversely, enhances the Benjamin-ian aura of this work of art?

Benjamin attributes social bases for the “contemporary decay of the aura” and that these “rest on two circumstances, both of which are related to the increasing significance of the masses in contemporary life.” [Section III] What are your thoughts on this?

While the contemporary cult of the Mona Lisa carries on in our modern fashion world today, Benjamin states that “originally, the contextual integration of art in tradition found its expression in the cult” and he clarifies, “in other words, the unique value of the ‘authentic’ work of art has its basis in ritual, the location of its original use value” and he proceeds with “an all-important insight: for the first time in world history, mechanical reproduction emancipates the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual.” Benjamin then points out a paradox that “to an ever greater degree the work of art reproduced becomes the work of art designed for reproducibility.” Cautioning, he qualifies this with: “But the instant that the criterion of authenticity ceases to be applicable to artistic production, the total function of art is reversed. Instead of being based on ritual, it begins to be based on another practice – politics.” [Section IV] Do you think the post-millennial function of art is one of ritual, politics or both? Can you cite examples of works of art to illustrate your point of view?

The Internet, and our use of it, are for us, in my opinion based upon Benjamin, the ultimate mechanical reproduction of art and exhibition space (another important concept to Benjamin). Acting as the mass which “is a matrix from which all traditional behavior toward works of art issues today in a new form” [Section XV] the Internet’s inherent mechanical reproduction is the ultimate emancipation of art, and I’d add, also its paradoxical enslavement of art to the new rituals of clicking, copying, pasting, scanning, uploading, downloading, swiping, posting, re-posting, tweeting, re-tweeting, liking, favorite-ing and deleting.

While it is easy for me to grasp the degradation of the Benjamin-ian aura in the work of art, because all one has to do is photocopy the Mona Lisa from an art book or copy it from a website and see the loss of resolution and aesthetic quality with each generation, one must ask rhetorically how Benjamin foresaw this without the benefit of Xerox, Photoshop, the World Wide Web, apps such as Instagram and filters. Do you find “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” as forward thinking as I do? Does it hold up in the digital age?

I cannot overlook that this provocation is assigned and intended for the readings for our Sept. 11 class, and it brings to mind some remarks made by the author of “Prozac Nation” Elizabeth Wurtzel. They struck me then and still do now, as reminiscent of the Epilogue in which Benjamin theorizes that war is the ultimate work of art. Wurtzel was asked about the events of Sept. 11, 2001 in February 2002 during an interview to promote her book More, Now, Again by the Toronto Globe and Mail in the context of her residency close to the World Trade Center, and she commented as follows: ‘I had not the slightest emotional reaction. I thought, this is a really strange art project…it was a most amazing sight in terms of sheer elegance. It fell like water. It just slid, like a turtleneck going over someone’s head.’ (Her comments set off a shock wave and likely caused her movie for “Prozac Nation” made by Miramax not to be released.) For me, these comments brought to mind words of Benjamin I have difficulty typing and relaying that “war is beautiful” and that “through gas warfare the aura is abolished in a new way.” Writing in his time and place, Benjamin quotes Fascism “Fiat ars – pereat mundus” (translation: let art be created, though the world perish) which was the Fascist spin on “l’art pour l’art” (art for art’s sake) and concludes by conjecturing “war to supply the artistic gratification of a sense of perception that has been changed by technology.” [Epilogue] Do you find this to be the logical and probable post-Marxian evolution?

Related Video Clip: Does this video of LVMH’s Titian window (detail from the painting of Mars, Venus and Cupid) decay its aura or enhance it?

Related Resources:

“Jeff Koons’s New Line” by Vanessa Friedman, The New York Times, April 11, 2017

“The Louis Vuitton x Jeff Koons Bags May Be My Least Favorite Designer Collab Ever” by Amanda Mull on purseblog, April 13, 2017

“Release Me” by John Harris, The Guardian, July 17, 2004

“Mona Lisa & an Iguana on 5th” by Carolyn A. McDonough, on CultureArtMedia, September 1, 2017