Born in 1924 to a father who didn’t finish high school and a mother with a two-year teaching certificate, Mina Shaughnessy earned her BA & MA from prestigious private universities: Northwestern and Columbia, respectively. For financial reasons, she did not pursue a Ph.D. Her modest rural roots, her reputable education, and her own frustration at not feeling free to attain the highest academic achievement provide context for the pioneering work she did at the end of her relatively short life in 1978, a year before Errors and Expectations was published.

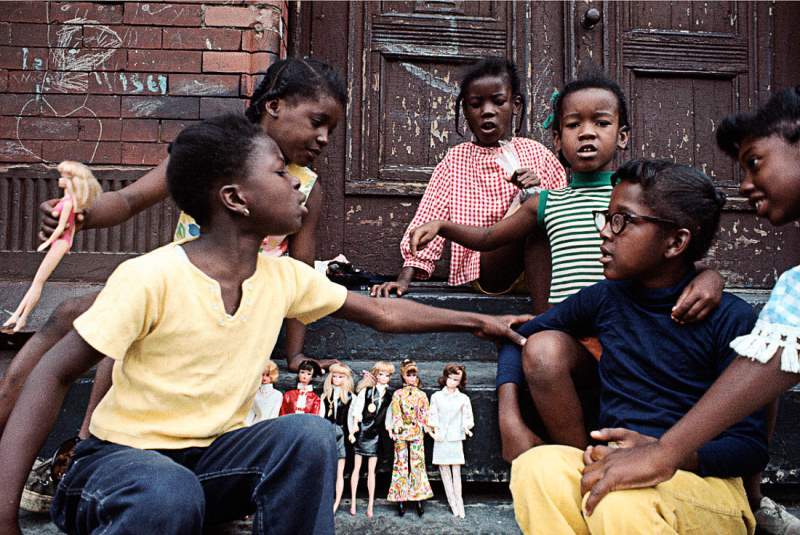

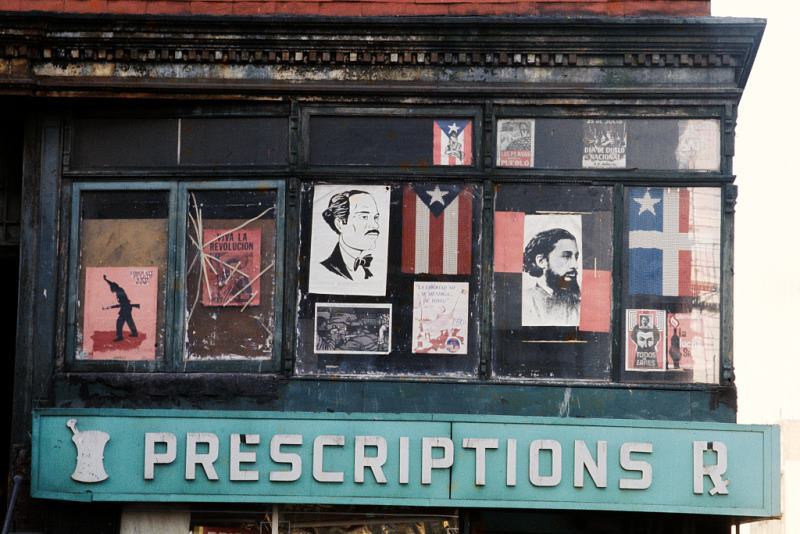

To get us in the mood of the time period, here are some photos of NYC in the 1970s, from Death, Destruction, And Debt: 41 Photos Of Life In 1970s New York.

East Harlem school children Camilo José Vergara Photographs

In Harlem, Black girls playing with white Barbies. Camilo José Vergara Photographs

1973 Central Park “Quilting Bee” a couple of miles south of Harlem The Atlantic

“Muggers Express…the most dangerous in the world” Business Insider

And in Brooklyn, an apartment with a “revolutionary theme.” Camilo José Vergara Photographs

There was much I found illuminating and sensitive in the introduction and chapter we read. I liked that Shaughnessy refers to her subjects as “writers,” rather than “students,” identifying them as already being what they are learning to be–perhaps unskilled, but not by default without ability or talent. She draws attention to teachers as also potentially being “unprepared,” putting the emphasis on their need to work hard, as well as on the students. She references feelings when she brings up tone, writing disintegration that escalates with frustration or fear, and how fraught academic might be a to a student, a “trap,” positioning the teacher as an adversary.

From one middle-aged, well-meaning white lady to another, what I wish Shaughnessy had addressed (from the introduction it does not appear that she did so elsewhere in the book) is race and ethnicity as a major theme in the writers’ lives, meriting more than the page three reference to the “racial and ethnic enclaves” “most” of the students were from. On the same page she refers to the “rules and rituals of college life,” but does not explore how vastly different these may be from these teenagers’ home lives and the fact that they are likely putting vast energy into code switching when they have not been give the college code book.

I observed that in the writing samples students capitalized “Black” (and not “white”), leading me to infer a race-consciousness in a time period on the heels of the establishment of racial, ethnic, and women’s studies departments. The National Council for Black Studies was founded in 1975, which was in the time period that Shaughnessy gathered her data. I do not necessarily fault Shaughnessy for sharing a less holistic view of first generation college life than might be prevalent in education literature today, but it is provocative to pedagogy studies today.

Questions to explore (feel welcome to add your own):

- Might learning to speak and write “white” be fraught for CUNY students?

- What other aspects of students lives might Shaughnessy have addressed, e.g., age, status as earners, family lives, activism, etc.?

- How could composition teachers embrace students in their totality?

- Should a teacher’s only focus be how they empart and improve skills?

- Are there different methods for teaching people of different races, ethnicities, genders, classes, etc.? Or only learning styles, e.g. Visual, Aural, Read/Write, Kinesthetic aka VARK?

Refer back to the photos above before you respond.

Jenna, thanks for this provocation and the pics! I would not know whether Shaughnessy was holistic enough (probably not), but I liked her piece anyway. Her introduction first, when she tries to navigate the pedagogical and political dilemma that comes with “errors” in higher education. If teachers – and the institutions, and the society – deem errors to matter, they somehow impose the “language of the masters” on students; if they don’t, they deprive their students of the sense of empowerment that comes with mastering the latter (drawing on Fanon’s thinking here). Shaughnessy makes yet another important point in her conclusion, as she hints at the need for teachers to change their assumptions regarding students making errors. Elbow’s piece, especially his focus on the psychology of correcting, offers a valuable follow-up to this discussion.

Has anyone from the class ever taken part in a WAC program? Any views on remedial writing classes? This week’s readings helped me grasp their purpose – nice timing, as I’ll be a WAC fellow next year. Reading Shaughnessy’s taught me that the social underpinnings of “making errors” and “poor writing” were acknowledged and addressed quite early on in US higher education. This was hardly the case in France, where making mistakes was and still is eliminatory in most competitive exams. We do have Bourdieu and his seminal work on social reproduction in education, but as far as I know, not much was ever done to redress these inequalities on the ground (no such things as remedial classes, for instance). The most widespread view is that if students can’t write correct French, it is on them and it merely means that higher education is not for them… As unfair as it is, my experience is that this assumption goes unquestioned and is internalized by virtually anyone involved, professors, students, and later on employers.

Jenna, thanks for this provocation. I recall New York City in 1975 and like how the photos you culled speak to the time. I think Shaughnessy was somewhat holistic in her analysis where “error” is concerned. She writes in the Intro “the errors…students make…cannot be neatly traced to one particular source [but rather] a number of interacting influences.” I did also find Shaughnessy’s pointing out that the interference error presents to the students’/writers’ “economy of effort” noteworthy.

Angelique, I enjoyed your comments to Jenna and I find it fascinating to hear the rigidity of the French system described. I experienced a parallel in Italy where I attended the University of Florence for one year. Although Italians are culturally flexible, the university system in Italy is not, and therefore it can take 5-7 years just to complete the equivalent to an American B.A. or B.S. degree.